Several years ago, over coffee, a friend admitted something odd to me: he had a “favorite fallacy.”

He didn’t like fallacies because he enjoyed being wrong, but because once he spotted it, he saw it everywhere—work meetings, news reports, even family arguments.

His favorite? The slippery slope.

“If we let students use calculators in middle school,” he said, “they’ll never learn math. Then they’ll fail in high school. Then society will collapse.” He laughed. “It’s absurd, but people believe it. And once you start looking for it, you see it everywhere.”

That conversation stuck with me, because it highlights something fascinating—the human brain isn’t wired for perfect logic. It’s wired for speed, shortcuts, and stories that feel true. Fallacies of thinking, or systematic errors in reasoning, are the fingerprints of that wiring. They show us where intuition collides with logic, where persuasion trumps precision.

What Are Fallacies of Thinking?

A fallacy is a faulty pattern of reasoning that leads to weak or unsound conclusions. They can be seductive because they often mimic the shape of good arguments. But look closely, and the cracks show.

They generally fall into two broad categories:

Formal fallacies: Errors in the structure of logic itself.

Example: If it rains, the ground gets wet. The ground is wet, therefore it rained.

Sounds neat, until you consider the sprinkler system.

Informal fallacies: Errors in the content, context, or use of evidence.

These include ad hominem attacks (attacking the person, not the argument), straw man arguments (misrepresenting someone’s position), or confirmation bias (only seeking evidence that supports what we already believe).

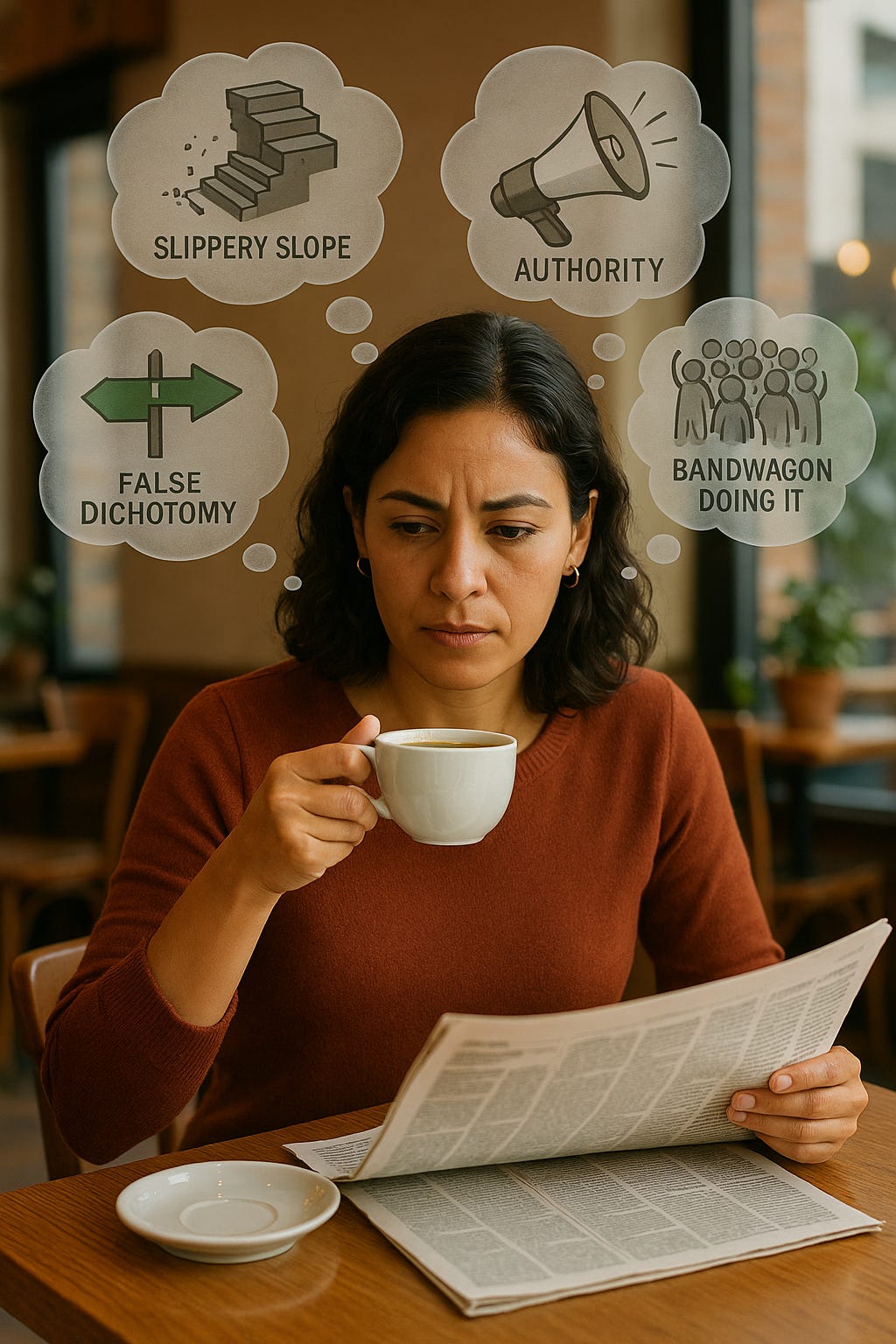

Common Fallacies We Bump Into Daily

We don’t just hear fallacies—we speak them. Here are some of the greatest hits, drawn from Bo Bennett’s book Logically Fallacious, with a few everyday examples:

False dichotomy: “Either you’re with me or against me.”

Slippery slope: “If we allow this one exception, chaos will follow.”

Appeal to authority: “A famous doctor said it, so it must be true.”

Hasty generalization: “I met two rude New Yorkers, so all New Yorkers are rude.”

Post hoc ergo propter hoc: “I wore my lucky socks, and we won. The socks worked.”

Bandwagon: “Everyone’s buying this stock—you should too.”

Red herring: “Sure, the policy has flaws, but what about the economy?”

Once you spot these, you’ll notice them everywhere on social media, in campaign speeches, marketing slogans, even around your own dinner table. It’s like learning a magician’s tricks. After a while, you can’t be fooled in the same way again.

Recognizing fallacies isn’t nitpicking—it’s self-defense.

Why It Matters

We live in a world where persuasion often matters more than truth. Politicians lean on fallacies to win votes. Marketers rely on them to sell products. Social media algorithms reward them because outrage spreads faster than reason.

If we don’t learn to notice, we risk being carried along by arguments that sound convincing but lack substance. But once you know the patterns, you can pause, probe, and think critically instead of reacting.

Conclusion: The Beauty of Being Wrong

Back to my friend and his “favorite fallacy.” At first, it seemed strange to enjoy spotting errors in reasoning. But now I see it differently. Learning to recognize fallacies is like learning a new language. The more fluent you get, the clearer the world becomes.

The truth is, we all fall into fallacies. We cut corners with our thinking. We lean on stories that feel true. We argue from authority, or imagine one small choice leading to inevitable disaster. However, in those mistakes lies an opportunity—not just to be right, but to be wiser.

Fallacies aren’t just flaws. They’re clues. And once you see them, you can’t unsee them.

So let me ask: what’s your favorite fallacy of thinking?

Because sometimes the most useful thing we can learn about the mind is not where it’s brilliant—but where it’s predictably, wonderfully, and consistently wrong.

Want to support without a paid subscription? Make a one-time donation below.