The Art of Noticing

Why Great Thinkers See What Others Miss

“Your brain will always try to finish the story. A good thinker waits for more of the story to unfold.”

One of the first things you learn as a leader is that people rarely show you the whole picture. One of the first things you learn as an educator is that the picture you think you’re seeing is almost always incomplete.

Both roles, a leader and an educator, demand a kind of disciplined curiosity; an ability to pause, observe, and ask, “What’s actually going on here?” rather than leaping to conclusions. Most people rush past this moment. However, effective educators and leaders slow down just long enough to notice the details that matter.

When I Misread the Moment

Years ago, I led a team that was struggling with morale. A project deadline was looming, communication was fraying, and the pressure was beginning to show. One afternoon, I walked into a meeting and saw one of my team members, let’s call him Jordan, sitting back in his chair, arms crossed, eyes down. He looked irritated. Disengaged. Uninterested.

I made a snap judgment: He’s checked out. He’s resisting the plan. He’s the problem. So I addressed the room with more urgency, more edge. I pushed harder. The energy sank lower. After the meeting, Jordan approached me and said quietly, “I’m trying, but I can’t track everything that’s happening. I want to help. I just need more clarity.”

In that moment, my entire interpretation of his body language cracked open. He wasn’t resisting. He was overwhelmed. And because I misread the moment, I led poorly.

The truth hit me hard:

Most leadership mistakes don’t come from a lack of skill. They come from a lack of accurate observation.

Weeks later, I watched a veteran educator handle a similar situation with a student. A boy was slouched in his chair, hood over his head, distant. Most teachers would read it as disrespect. But this teacher didn’t judge immediately; she observed. She asked a single, gentle question: “You good today?” The student nodded, then whispered, “My mom’s in the hospital.”

Two identical postures. Two completely different realities. That was the moment I realized:

Educators aren’t just teaching content; they’re interpreting human behavior with incredible accuracy and care. And the same thinking skill that makes them effective is the one leaders desperately need.

Why We Miss What’s Right in Front of Us

Cognitive psychologists have been studying this for decades. The New York Times and NPR have both highlighted research on “inattentional blindness,” the phenomenon where we overlook obvious information because we’re focused on the wrong thing. The famous “invisible gorilla” experiment showed that when people are told to watch basketball players passing a ball, half miss a person in a gorilla suit walking straight through the scene.

If we can miss a gorilla, imagine how easily we can misread a colleague’s frustration or a child’s anxiety.

Researchers at the Harvard Graduate School of Education call this skill “teacher noticing”: the ability to interpret subtle cues, identify patterns, and respond with insight rather than assumption. But this isn’t just for teachers. Anyone who leads people relies on the same cognitive process:

noticing without judging,

pausing before interpreting,

and seeking context before reacting.

Outstanding leadership is impossible without great noticing.

The Power of Observing Without Jumping to Conclusions

Educators learn early that the first explanation is rarely the correct one:

A student who won’t sit still might not be defiant. He might be anxious, hungry, or confused.

An adult who seems irritated might not be disrespectful. They might be carrying stress, fear, or uncertainty.

When we interpret too quickly, we stop thinking. When we observe deeply, our thinking becomes sharper. The difference between the two is a simple mental habit, but it changes everything.

The Educator’s Lens

As an educator and administrator, I have had to conduct countless classroom observations. Over the years I have learned that the quality of my obseravtion and feedback to teachers is directly connected to my ability to notice the full context of what is happening in the classroom. From my expereinces I have summarize my observation approach to the following four-step method for noticing more accurately.

Observe without judging.

Describe what you see, not what you assume. “Jordan has his arms crossed and isn’t making eye contact.” (Not: “Jordan is upset.”)

Name only what is observable.

Stick to sensory details—tone, posture, behavior.

Seek context before responding.

“What else might be true?” “What information am I missing?”

Respond based on evidence, not assumptions.

This is how teachers avoid mislabeling students… and how leaders avoid misjudging people.

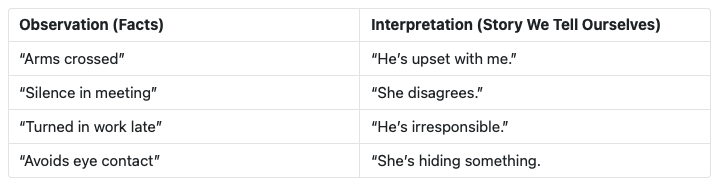

Observation vs. Interpretation

The left column is information. The right column is imagination. The best thinkers know the difference.

Why This Matters for Better Decision-Making

Good decisions require accurate information. Accurate information requires accurate observation.

When leaders fail to notice what matters:

problems escalate,

relationships weaken,

and decisions become reactive instead of intentional.

When educators fail to notice what matters:

students slip through the cracks,

behaviors get mislabeled,

and opportunities to support growth are missed.

Noticing isn’t passive. It’s an act of leadership. It’s the foundation of wisdom. And it’s the first skill anyone needs to become a great thinker.

Want to support without a paid subscription? Make a one-time donation below.