Leading with the Whole Brain

Rethinking How We Lead and Learn in Higher Education

Higher education loves intellect—but often forgets about thinking.

We build committees, task forces, and strategic plans, but rarely pause to ask: How are we thinking about this?

That question might be the most powerful leadership tool we have.

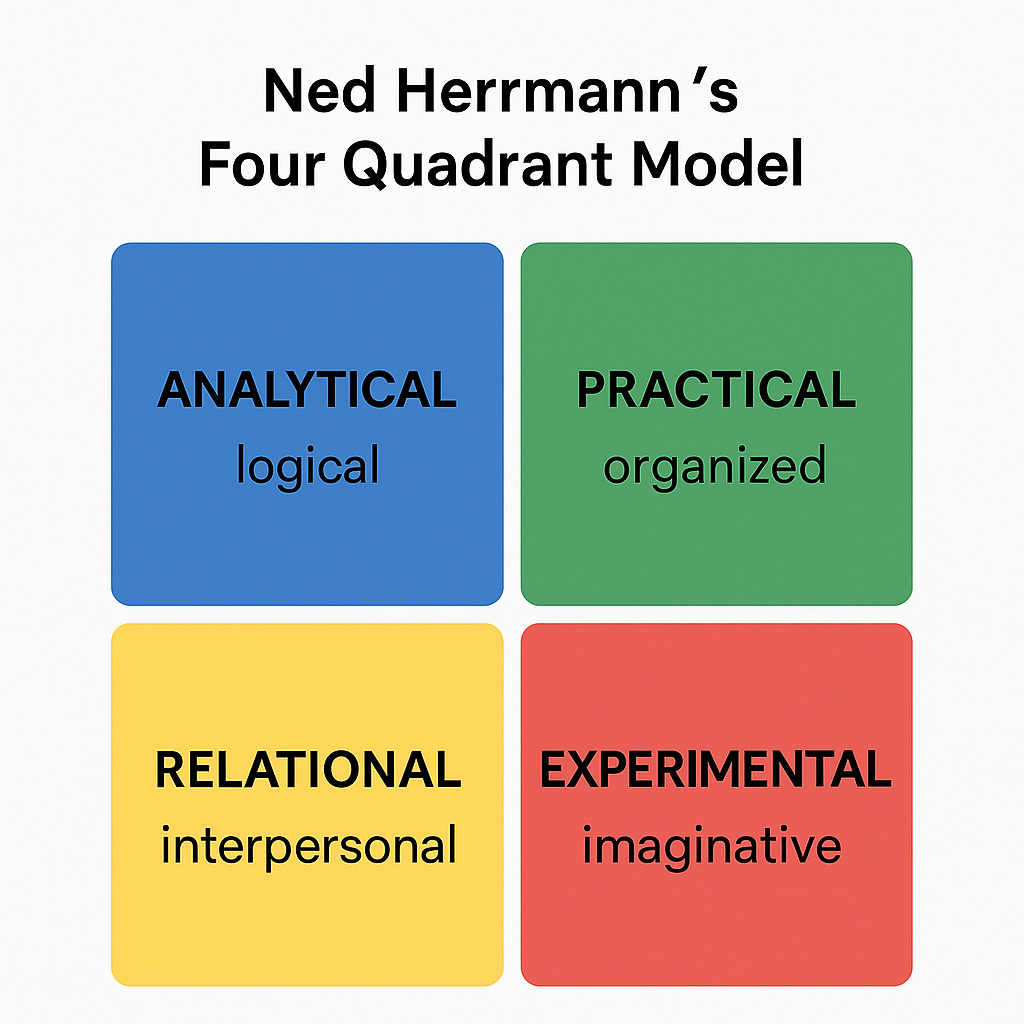

In the late 1970s, Ned Herrmann developed what he called the Whole Brain® Model—a framework that mapped how people process information, make decisions, and solve problems. It wasn’t neuroscience in the clinical sense; it was cognitive cartography.

And for leaders in higher education, it offers a way to see what’s often invisible: the diversity of thought that shapes every meeting, policy, and innovation.

The Four Thinking Styles—and Why They Matter

Herrmann identified four dominant modes of thinking: Analytical, Practical, Relational, and Experimental.

Think of them less as boxes and more as lenses—each clarifies certain truths while blurring others.

Analytical thinkers value logic, precision, and evidence. They ask for the data before they decide.

In academia, they’re the methodologists, the skeptics, the people who anchor vision in verification.

Practical thinkers bring order to complexity. They organize, structure, and plan.

They’re the ones who turn abstract ideas into actionable roadmaps and make sure the report actually gets submitted.

Relational thinkers are the emotional compass of the group. They sense the room, bridge divides, and keep humanity at the center of hard decisions.

They remind us that institutions are made of people, not processes.

Experimental thinkers live in possibility. They imagine what’s next, connect ideas across disciplines, and see patterns others miss.

The truth is, we all have access to all four modes—but most of us prefer one or two.

Leadership begins with knowing which part of your brain you lead from—and who you need around you to complete the circle.

When Thinking Styles Collide (and Complement)

Picture a familiar scene: a budget meeting during a financial downturn.

Your CFO, Dr. Sarah Martinez, leads with analytical precision—charts, models, projections.

Her clarity keeps emotion out of decision-making. But when someone suggests keeping a struggling program for its community value, she pauses. The numbers say one thing. The human story says another.

Now enter James Chen, the associate provost. A practical thinker to his core.

He’s the one who translates vision into timelines, compliance checklists, and task owners. Without him, strategy remains a whiteboard fantasy. But if James runs the show alone, creativity suffocates under structure.

Then there’s Dr. Lisa Thompson, a dean leading a department merger. Her relational intuition makes her start not with policy, but with people—listening before reorganizing. She knows that resistance to change isn’t defiance; it’s fear of being unseen.

Her empathy turns chaos into cohesion.

And finally, Dr. Marcus Williams, the academic provost who wants to reimagine general education.

He sketches ideas that sound impossible—interdisciplinary “challenge pathways,” redefined majors, courses co-taught across divisions. To some, it sounds utopian. But his wild ideas plant seeds the institution will one day call innovation.

Each of them, brilliant in isolation, but together-Transformational.

Herrmann’s insight wasn’t just cognitive—it was organizational.

Higher education’s toughest problems don’t have single-quadrant solutions.

Strategic planning needs analytical clarity, practical design, relational engagement, and experimental courage.

Crisis management demands all four—data, logistics, empathy, and creative problem-solving.

Diversity and inclusion work best when driven by evidence, structure, humanity, and imagination in equal measure.

When leaders understand this, something shifts.

They stop seeing cognitive differences as friction and start seeing them as fuel.

Whole brain thinking starts with self-awareness.

Ask yourself:

Which mode feels most natural to me? Which one do I avoid?

An analytical leader might need to pause before dismissing emotion as bias.

A relational leader might need to ground compassion in data.

A visionary might need a pragmatist at their side.

Next, look at your team composition.

If everyone thinks like you, your meetings will feel harmonious—and your ideas will stagnate.

Cognitive diversity isn’t just inclusion of thought; it’s insurance against collective blindness.

When a practical thinker asks, “What’s the plan?”, they’re not resisting innovation—they’re anchoring it.

When an analytical colleague pokes holes in your big idea, they’re pressure-testing it for survival.

When a relational leader slows the process to ensure trust, they’re buying long-term momentum.

The more fluently you speak across thinking styles, the more aligned—and adaptable—your institution becomes.

The Deeper Lesson

Cognitive diversity is not just a leadership tool; it’s a form of wisdom.

Higher education celebrates intellectual diversity in scholarship, yet too often ignores diversity in how we think.

The best leaders don’t just lead with their strongest quadrant—they lead with the whole brain.

They combine rigor with empathy, structure with creativity.

They build cultures where data meets meaning, and innovation meets discipline.

In a world where change is constant, whole brain leadership isn’t optional—it’s the mindset that keeps higher education human, adaptive, and alive.

Want to support without a paid subscription? Make a one-time donation below.