Cognitive Biases in the Classroom and the Boardroom

How leaders and educators master bias-awareness

The moment you start working with people, you inherit their complexity. Their histories, assumptions, fears, habits, hopes, and insecurities walk into the room with them. But the same thing is true of you. Every decision you make is filtered through your own invisible lens—your cognitive biases.

Educators confront these biases every day. Leaders confront them too. Most people don’t even realize they’re there. But ignoring them doesn’t make them disappear. In fact, it makes them stronger.

This chapter explores how our mental shortcuts, useful in some moments and disastrous in others, shape our judgments, interactions, and decisions far more than we’d like to admit.

Two People, One Bias

Early in my career, a new student walked into my classroom mid-semester. Within minutes, I made snap assumptions about him: unfocused, unprepared, maybe even uninterested. He didn’t write anything down, avoided eye contact, and let out an impatient sigh when asked a question.

Years later, I watched the same phenomenon unfold in a leadership context. A colleague gave short, clipped responses in a meeting. I assumed she was frustrated with me. I replayed the interaction all afternoon, building a story in my head. When I finally asked her about it, she said, “Oh, I’m sorry. I had a migraine coming on.”

Again, my assumption wrote a story that reality didn’t support. Humans are meaning-making machines. When we don’t have information, we create it. This is the birthplace of cognitive bias.

Why Our Brains Take Mental Shortcuts

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman famously described two modes of thinking:

System 1: fast, instinctive, automatic

System 2: slow, analytical, deliberate

Most of our daily thinking happens in System 1, because it’s efficient. However, System 1 has a flaw. It relies on mental shortcuts rather than careful reasoning. These shortcuts can help us make quick judgments, but they also cause us to misjudge, misinterpret, and mislead ourselves. Research from The Atlantic, Harvard Business Review, and decades of cognitive science confirms a simple truth:

Biases don’t mean your thinking is broken. They mean your brain is on autopilot.

Educators and leaders who excel learn to notice when autopilot is steering the wheel and when to take back control.

Three Biases That Shape Our Decisions

There are dozens of cognitive biases, but three show up repeatedly in both classrooms and leadership environments.

Confirmation Bias: Seeing Only What Confirms Your Beliefs

You believe a student is unfocused, so every small action “proves” it. You think a colleague is resistant, so every hesitation “confirms” it. Nothing is more dangerous than an expectation looking for evidence. Confirmation bias narrows your vision until you only notice what reinforces your assumptions. Everything else becomes invisible.

Educators see this all the time:

A “quiet kid” gets overlooked.

A “rowdy kid” gets blamed quickly.

A “high-performing kid” gets a pass even when they’re struggling.

Leaders see it too:

“He’s not leadership material.”

“She’s difficult.”

“This plan can’t work.”

Pre-judgment is the enemy of accurate judgment.

Fundamental Attribution Error: Blaming Character Instead of Context

When someone else makes a mistake, we assume it reveals their personality, but when we make a mistake, we blame the situation. Students who forget homework become “irresponsible.” Employees who miss a detail become “careless.” But when we forget something, we say things like, “Oh, I’ve just had a lot going on.” This bias blinds us to the pressures, obstacles, and complexities other people carry.

Research in social psychology shows that humans routinely underestimate situational factors, even when the evidence is right in front of us. Educators learn to ask, “What happened before this behavior?” Leaders need to ask the same.

The Halo and Horns Effects: First Impressions Take Over

If a student gives a great first impression, everything they do looks better. If an employee makes one early mistake, everything they do feels questionable. Educators learn quickly that the “aura” surrounding a student can become self-fulfilling.

Leaders fall into the same trap. We are too generous with some people and too critical with others. And usually, we’re not even aware we’re doing it. The Halo and Horns effects turn our initial impressions into ongoing judgments; ones that distort reality long after the moment has passed.

What Bias Costs Us

Unchecked bias leads to inaccurate decisions, unnecessary conflict, misaligned expectations, missed talent, and broken trust. But the greatest cost is internal because we stop thinking deeply, questioning ourselves, and seeing people clearly. Bias doesn’t just limit your perception, it limits your leadership.

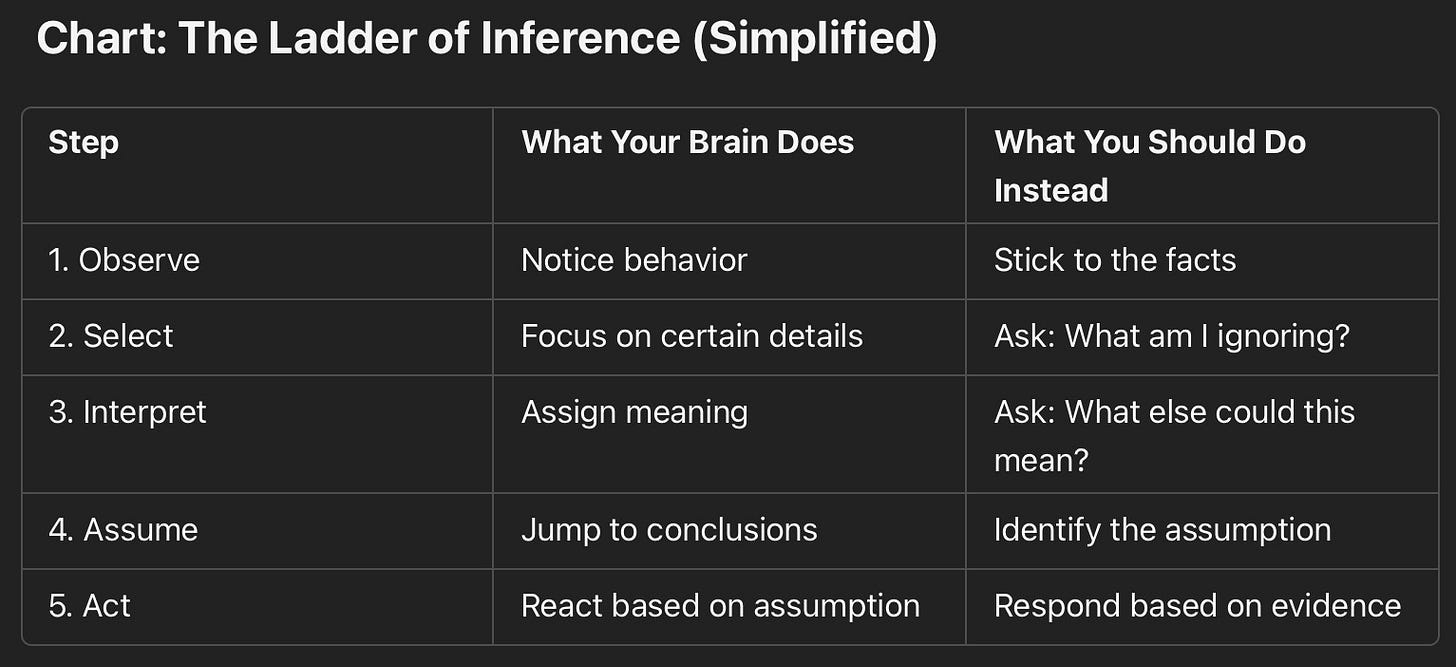

The Bias Check Cycle

A simple, powerful method for thinking more accurately. Educators use this instinctively. Leaders should use it intentionally.

What assumption am I making?

Name it explicitly.

What evidence do I actually have?

Separate the facts from the story.

What else could be true?

Generate at least three alternate explanations.

What information am I missing?

Identify the gaps in your understanding.

What’s the most generous accurate interpretation?

Not an excuse, an alternative.

How can I check this without judgment?

Ask a clarifying question, invite context, a gather real information.

This simple cycle changes interactions, improves decisions, and strengthens relationships.

Most conflict happens between steps 3–5. Most solutions happen when we return to step 1.

The Leadership Advantage of Checking Your Bias

Leaders and educators who master bias-awareness gain powerful advantages as they usually don’t overreact, mislabel people, or escalate small issues into big ones. Instead, they create environments where people feel understood instead of judged, and make decisions based on reality instead of projection. The key is, bias doesn’t disappear. But good thinkers learn to interrupt it.

Want to support without a paid subscription? Make a one-time donation below.

This is concept insightful, yet simple. The checklist is great for all educators, but can be a powerful resource for pre-service and novice teachers.

Very insightful post! 🌸